Links

4 stars

Paul McCartney Doesn’t Really Want to Stop the Show | New Yorker

Early evening in late summer, the golden hour in the village of East Hampton. The surf is rough and pounds its regular measure on the shore. At the last driveway on a road ending at the beach, a cortège of cars—S.U.V.s, jeeps, candy-colored roadsters—pull up to the gate, sand crunching pleasantly under the tires. And out they come, face after famous face, burnished, expensively moisturized: Jerry Seinfeld, Jimmy Buffett, Anjelica Huston, Julianne Moore, Stevie Van Zandt, Alec Baldwin, Jon Bon Jovi. They all wear expectant, delighted-to-be-invited expressions. Through the gate, they mount a flight of stairs to the front door and walk across a vaulted living room to a fragrant back yard, where a crowd is circulating under a tent in the familiar high-life way, regarding the territory, pausing now and then to accept refreshments from a tray.

Their hosts are Nancy Shevell, the scion of a New Jersey trucking family, and her husband, Paul McCartney, a bass player and singer-songwriter from Liverpool. A slender, regal woman in her early sixties, Shevell is talking in a confiding manner with Michael Bloomberg, who was the mayor of New York City when she served on the board of the Metropolitan Transportation Authority. Bloomberg nods gravely at whatever Shevell is saying, but he has his eyes fixed on a plate of exquisite little pizzas. Would he like one? He narrows his gaze, trying to decide; then, with executive dispatch, he declines.

McCartney greets his guests with the same twinkly smile and thumbs-up charm that once led him to be called “the cute Beatle.” Even in a crowd of the accomplished and abundantly self-satisfied, he is invariably the focus of attention. His fan base is the general population. There are myriad ways in which people betray their pleasure in encountering him—describing their favorite songs, asking for selfies and autographs, or losing their composure entirely.

3 stars

Dictator Book Club: Orban | Astral Codex Ten

Some are born great. Some achieve greatness. And some are Victor Orban's college roommates.

Orban: Europe's New Strongman and Orbanland, my two sources for this installment of our Dictator Book Club, tell the story of a man who spent the last eleven years taking over Hungary and distributing it to guys he knew in college. Janos Ader, President of Hungary. Laszlo Kover, Speaker of the National Assembly. Joszef Szajer, drafter of the Hungarian constitution. All of them have something in common: they were Viktor Orban's college chums. Gabor Fodor, former Minister of Education, and Lajos Simicska, former media baron, were both literally his roommates. The rank order of how rich and powerful you are in today’s Hungary, and the rank order of how close you sat to Viktor Orban in the cafeteria of Istvan Bibo College, are more similar than anyone has a right to expect.

Our story begins on March 30 1988, when young Viktor Orban founded an extra-curricular society at his college called The Alliance Of Young Democrats (Hungarian abbreviation: FiDeSz). Thirty-seven students met in a college common room and agreed to start a youth organization. Orban's two roommates were there, along with a couple of other guys they knew. Orban gave the pitch: the Soviet Union was crumbling. A potential post-Soviet Hungary would need fresh blood, new politicians who could navigate the democratic environment. They could get in on the ground floor.

It must have seemed kind of far-fetched. Orban was a hick from the very furthest reaches of Hicksville, the “tiny, wretched village of Alcsutdoboz”. He grew up so poor that he would later describe “what an unforgettable experience it had been for him as a fifteen-year-old to use a bathroom for the first time, and to have warm water simply by turning on a tap”. He was neither exceptionally bright nor exceptionally charismatic.

Still, there was something about him. To call it "a competitive streak" would be an understatement. He loved fighting. The dirtier, the better. He had been kicked out of school after school for violent behavior as a child. As a teen, he'd gone into football, and despite having little natural talent he'd worked his way up to the semi-professional leagues through sheer practice and determination. During his mandatory military service, he'd beaten up one of his commanding officers. Throughout his life, people would keep underestimating how long, how dirty, and how intensely he was willing to fight for something he wanted. In the proverb "never mud-wrestle a pig, you'll both get dirty but the pig will like it", the pig is Viktor Orban.

2 stars

Unraveling the evidence about violence among very early humans | Cold Takes

As I've asked Has Life Gotten Better?, I've run into some intense debates about how violent early humans were. […]

Trying to unravel and understand the points of disagreement has been confusing, but necessary to get a decent picture of trends in quality of life over very long time periods. The rate of violent deaths is one of the few systematic, meaningful-seeming metrics for assessing quality of life before a couple hundred years ago, and strong claims are made on both sides.

As of now, I believe a different story than either "violent death rates have consistently gone down over time" or "early societies were remarkably peaceful." […]

My current overall guess: after violent death rates ~doubled with the transition from nomadic to sedentary societies, they then fell back to the original rates (but not necessarily much below) at some point in between then and the kind of modernization that came with court records and made homicide rate estimates possible. After that sort of modernization, they fell fairly steadily, as shown in the above charts. […]

The story for "overall quality of life" looks broadly similar to the story for violent death rates: things look like they got worse around 10,000 BCE (when agriculture was developed), then we have a big mystery between then and the early 2nd millennium, and since then there was some improvement (which accelerated in the Industrial Revolution a couple hundred years ago). This is a different picture from either "Life has gotten steadily better throughout our history" or "Life was best in the state of nature," both of which I think are more common memes.

Soccer Looks Different When You Can’t See Who’s Playing | FiveThirtyEight

During the 2018 World Cup, Zito Madu pointed out the racially coded language commentators used to describe a match between Poland and Senegal, which didn’t line up with what he saw on the field. A typical article claimed that “‘Poland struggled all game against the pace and physicality of Senegal,’ which is an absurd line for anyone who watched the game,” Madu wrote in SB Nation. It felt like an example of a widespread tendency to focus on Black players’ “pace and power” while praising white players for things like intelligence and work ethic.

But how would the same game have looked to viewers who literally couldn’t see race?

Sam Gregory was working for the Canadian data provider Sportlogiq a couple of years ago when Toronto FC director of analytics Devin Pleuler came to him with an idea. The company’s broadcast tracking technology can capture how players move their limbs and reproduce their stick-figure skeletons in a two-dimensional render. If Gregory’s Sportlogiq colleagues and Pleuler showed the same clips to different viewers as either a video or an anonymized animation, they could measure how attitudes toward race and gender affect how we see soccer.

Early Civilizations Had It All Figured Out | New Yorker

I don’t really believe this, but it’s interesting nonetheless:

A contrarian account of our prehistory argues that cities once flourished without rulers and rules—and still could.

1 star

Why do dogs tilt their heads? New study offers clues | Science

“Gifted” dogs often make the gesture before correctly identifying a toy

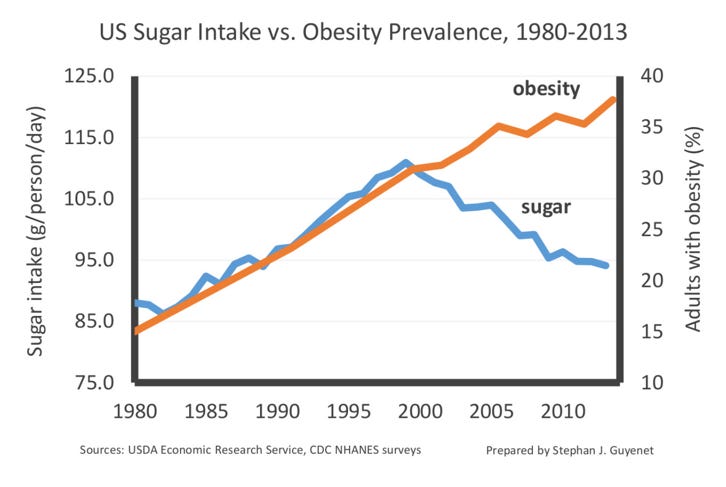

Sugar Consumption | Marginal Revolution

From Paul Kedrosky this graph which casts doubt on a sugar mono-causal theory of obesity. Yes, it includes corn syrup.