Links

3 stars

Your Book Review: The Accidental Superpower | Astral Codex Ten

Fascinating and just the slightest bit troubling:

In The Accidental Superpower: The Next Generation of American Preeminence and the Coming Global Disorder (2014), Peter Zeihan predicts the future of world politics and economic development in a way that an ACX fan would appreciate. He puts a timeline on it. The book isn’t about “some hazy distant future after we’re all dead and gone, but the future we will all be living in for the next fifteen years of our lives.” Zeihan’s subtitle hints at his big and bold thesis, which predicts “the dissolution of the free trade order, the global demographic inversion, the collapse of Europe and China,” which “is all just a fleeting transition” to a world largely abandoned by America. […]

As we saw with his exposition on the Nile, Zeihan puts a lot of emphasis on the value of river systems. He argues that America’s waterway network alone should be sufficient for “global dominance.” The numbers he provides in support of this point are impressive. For example, “the Mississippi is only one of twelve major navigable American rivers. Collectively, all of America’s temperate-zone rivers are 14,650 miles long. China and Germany each have about 2,000 miles, France about 1,000. The entirety of the Arab world has but 120.” He praises US barrier islands that mitigate oceanic destruction and effectively create another river system, as well as the fact that the river system is an actual network. All of this gives America more internal waterways than the rest of the world combined. Thus, we get cheap transportation for “Nebraska corn or Tennessee whiskey or Texas oil or New Jersey steel or Georgia peaches or Michigan cars,” enabling savings that “can be used for whatever Americans (or their government) want, from iPhones to aircraft carrier battle groups.” America doesn’t have to spend on artificial infrastructure, like German roads and rails, but when it does, the competition from the rivers keeps transport costs low. […]

Zeihan provides a reminder that national security is actually a thing, and that at its most basic level, it’s about protection against invasions. It was something of a shock reading about America’s land borders in that context. “As Santa Anna discovered during the Texas Independence War, there is no good staging location in (contemporary) Mexican territory that could strike at American lands.” And, “Canada’s border with the United States is much longer, more varied, and even more successful at keeping the two countries separated,” thanks to mountains and thick forests over much of it. The mid-continent lands are much more connected, but Zeihan frames these Canadian areas as basically American; they’re physically separated from Canada’s core eastern provinces, so trade with them is weaker than with the closer American states.

Then there are the oceans. As much as Zeihan loves deserts for protection, he loves oceans more (particularly in a post-World War II world; more on that below). We get a story about the War of 1812 nearly splitting America into three when the British attacked Baltimore. America learned about “strategic vulnerability and sea approaches,” as the attack “on Baltimore—indeed, the entire war effort—would have been impossible without launching grounds in Canada and the Caribbean.” American foreign policy since then can be understood with respect to this lesson. Zeihan cites it as inspiration for America’s steps to make its ocean borders truly impenetrable, such as working to sever Canada from Britain, and the imperial-era acquisitions of Alaska, Hawaii, Midway, Puerto Rico, and de facto control of Cuba (preventing enemies from cutting off Mississippi River-based trade from the rest of the world). […]

The second half of The Accidental Superpower is filled with Zeihan’s predictions about what happens if the big thesis is right. Some states will fail, as they don’t have what’s needed to survive (Syria, Greece, Libya). Some will decentralize, as they’re in the same boat, just not as hard up (Russia, China). Some will merely decline, as they have some capacity to address challenges (Brazil, India, Canada). Some will cope (UK, France, Peru, Philippines). A few will join the US as “masters of the chaos,” as they have favorable geographies and other advantages (Australia, Argentina, Angola, Turkey, Indonesia, Uzbekistan). […]

Europe’s problems appear awful. “A continent riven by war is hardly how most of us think of Europe, but that is because the Europe we know has been transformed utterly by Bretton Woods,” which is the only thing that has ever united Europe from a security perspective. Zeihan sees America going away from Europe, and therefore the old conflicts will resume. The result will include countries afraid of an older Germany that faces economic catastrophe (its demographic pyramid is bad, with a rapidly-aging population that will soon retire, and its export-driven economy is in danger), the above-mentioned threats from Russia, “a justifiably paranoid Poland backed by a no longer neutral Sweden,” and a rising Turkey. While Zeihan doubts that each of these problems will lead to wars, “it truly would be stunning if none of them did.”

The future of war is bizarre and terrifying | Noahpinion

If that put you in a bad mood, this won’t help things:

Like in the interwar years, we’ve been racing to invent new military technologies, but we haven’t yet had a chance to use them to their full capability. And yet the mere creation of these technologies, like the invention of the aircraft carrier, seems like it alters the international balance of power in ways that make us more likely to try out the new weapons and see where things stand.

But what’s also worrying is how many of the new military technologies are specialized for use off the battlefield. […]

But the scariest possibility might be assassination drones. As dramatized in the 2017 film Slaughterbots, autonomous quadcopters might fly around looking for someone’s face in order to kill them. Range is currently a big limitation for this sort of attack, but as energy technology improves, this sort of thing might get very scary. And unlike other military drone applications, assassin drones wouldn’t confine themselves to a traditional battlespace, or even traditional wartime; they would be a lurking, looming, omnipresent threat. […]

Which leaves the disturbing possibility that nations might simply exist in a state of low-grade cyberwarfare at all times, attempting to disable each other’s infrastructure as a matter of course. As long as the damage is purely economic and doesn’t immediately and violently kill anyone (e.g. hacking air traffic control systems to cause plane crashes), this constant warfare might become part of daily life, with infrastructure and computer systems just failing at random times.

Already, China and Russia seem intent on bringing something like this about, and other countries are racing to improve their capabilities to catch up. […]

The world may yet explode into another WW2-style conflagration, or the kind of nuclear holocaust we feared during the Cold War. If so, then my bet is that drones will dominate that battlefield. But most of the modern military technologies led themselves to a very different kind of great-power war — a war of constant sniping and harassment. Assassin drones, cyberattacks, info ops, and bioweapons raise the possibility of never-ending low-grade attacks that are below the threshold of massive retaliation.

The Anxiety of Influencers | Harper’s Magazine

Maybe ignorance is bliss:

It’s noon in Los Angeles toward the end of the Plague Year, and I’m lounging on the patio of a swanky three-floor mansion, watching a scrum of teenage boys perform trending TikTok dances. Arranged in a tidy delta formation near the jacuzzi and pool, the five boys smile into the glare of a ring light, at the center of which is affixed a smartphone recording their moves. These boys possess a teenybopper cuteness and, because they’re between the ages of eighteen and twenty, they have noisomely strong metabolisms and thus go shirtless pretty much all of the time, displaying either the ectomorphic thinness of trees or greyhounds or, in one boy’s case especially, the sharply delineated musculature of a really big insect. They bite their lower lips, and their expressions are—I’m sorry, there’s no other way to describe them—precoital. […]

Also known as content houses or TikTok mansions, collab houses are grotesquely lavish abodes where teens and early twentysomethings live and work together, trying to achieve viral fame on a variety of media platforms. Sometime last spring, when most of us were making bread or watching videos of singing Italians, the houses began to proliferate in impressive if not mind-boggling numbers, to the point where it became difficult for a casual observer even to keep track of them. […]

Now, on the pool deck, the boys tussle and roughhouse with the zeal of Labrador puppies, slugging each other lovingly in the shoulders and then retreating with giggles like ninnies. As one boy gets chased, he shrieks, “Yo, bro, bro! I was just kidding!” They’re so caught up in their own antics that they hardly even notice my presence. In this way, I can float among them like a ghost in a Henry James novel, loitering on the edge of the patio as they arrange a post for Instagram. In some sense, they are like college boys anywhere, except that they live in a seven-thousand-square-foot mansion, a residence whose value is roughly $8 million and whose rent is $35,000 a month—which, it must be said, is more than half of what I make in a year as a tenure-track university professor.

The pool deck looks out on the undulant topography of Beverly Hills, with the steeple tops of pine trees etched in the distance. All this would seem idyllic if it weren’t for the noxious blots of smoke from the wildfires that have been enshrouding California, which lend the sky a kind of disaster-movie ominousness. The West Coast is on fire. Fifty thousand Americans are contracting COVID every day, and the economy is drawing ever closer to a very steep precipice. Against this apocalyptic backdrop, it’s been strange to watch these kids gambol and twirl, since it reminds you of nothing so much as Nero and his fiddle. When I ask the boys whether they’re concerned about the state of the Republic, they rub their noses and look up from their phones. “What? Nah, man,” one says. “Things are getting better every single year.”

Into the Mystical and Inexplicable World of Dowsing | Outside

For centuries, dowsers have claimed the ability to find groundwater, precious metals, and other quarry using divining rods and an uncanny intuition. Is it the real deal or woo-woo? Dan Schwartz suspends disbelief to see for himself. […]

Bull would not realize for some time that what he had done that Easter Sunday was to channel the other side—the spirit world, as he calls it—which always felt strongest when he was close to Mother Nature, when the din of his world hushed and the messages from the other side rose in him like goose bumps. He would not learn until his twenties that he could call upon the hush to find things—water, minerals, utility lines—on a map; he would be in his forties before he learned to summon from the silence images of missing people or lost pets or misplaced wedding rings; and not until he was a half-century old would he realize, with shock, that on rare days he could project visions onto the landscape to guide him in his search, like the time a golden grid of shimmering lines snapped above the grass and led him to a well site. Bull’s calling, he would learn, was in finding things the old way, with his intuition as a guide and a forked stick as a pointer, like dowsers have for centuries. All his powers would come in time. It was on that Easter Sunday, when Bull was just a boy, that he took the first step: he learned to find water. […]

Detractors say it’s all hooey. Science has shown that hidden desires can move your muscles subconsciously, and this is why the rods point and the pendulums swing. (This “ideomotor effect” also explains Ouija boards.) Successes are exceptions. Dowsers are charlatans who more often fail to find what they seek, or find it by dumb luck.

Many of those who hire a dowser say they don’t know how the magic works, only that it does. “It’s just—insane,” says Steven Strong, a homeowner in Vermont’s Upper Valley. “I’m an engineer. I know physics. I can’t explain any of it.” But when the well on his property stopped producing about five years ago, the man Strong contracted to drill a new one had no idea where to put it. (Drillers don’t locate the water; they only strike it.) At the driller’s recommendation, Strong hired a dowser, a man from up north named Steve Herbert.

He watched Herbert circle his property for some time. Then, about 50 feet from the dried-up well, the dowser hammered a stake into the earth. He proclaimed that, if placed right here, perfectly vertically, the rig would hit a spring that gushed 25 gallons per minute of good, clean water. The driller drilled. Water rushed. “Honest to goodness, without any embellishment,” Strong said, “it was exactly spot-on. Not 23.5. Not 26. But 25 gallons a minute. I was there and I didn’t believe it, and the well driller was slack-jawed.”

2 stars

What My Korean Father Taught Me About Defending Myself in America | GQ

Born in 1939 during what would be the last years of the Japanese colonial occupation of Korea, my father, Choung Tai Chee, also called Charles or Chuck or Charlie, came to the United States in 1960. He was flashy, cocky, unafraid, it seemed, of anything. Wherever we were in the world, he seemed at home, right up until near the end of his life, when he was hospitalized after a car accident that left him in a coma. Only in that hospital bed, his head shaved for surgery, did he look out of place to me.

A tae kwon do champion by the age of 18 in Korea, he had begun studying martial arts at age 8, eventually teaching them as a way to put himself through graduate school, first in engineering and then oceanography, in Texas, California, and Rhode Island. He loved the teaching. The rising popularity of martial arts in the 1960s in Hollywood meant he made celebrity friends like Frank Sinatra Jr., Paul Lynde, Sal Mineo, and Peter Fonda, who my father said had fixed him up on a date with his sister, Jane, in the days before Barbarella. A favorite photo from his time in Texas shows him flying through the air, a human horseshoe, each of his bare feet breaking a board held shoulder high on each side by his students. […]

Only when I was older did I understand the warning about being strong enough to swim to shore in another context, when I learned the boat he and his family had fled in from what was about to become North Korea nearly sank in a storm. In Seoul as a child, he scavenged food for his family with his older brother, coming home with bags of rice found on overturned military supply trucks, while his father went to the farms, collecting gleanings. His attempts to teach me to strip a chicken clean of its meat make a different sense now. I had thought of him as an immigrant without thinking about how the Korean War made him one of the dispossessed, almost a refugee, all before he left Korea.

When I began getting into fights as a child in the U.S., he put me into classes in karate and tae kwon do for these same reasons. He loved me and he wanted me to be strong. I just wasn’t sure how I was supposed to take on a whole country.

Yes, lockdowns were good | Noahpinion

So anyway, Americans generally resisted lockdowns. And mobility data show that Americans didn’t even really follow the weak, patchy, and temporary lockdowns we put in place.

So this entire post is a moot point. Lockdowns failed. A bunch of us died, until eventually we got vaccines. This post doesn’t really matter at all. But now that the evidence is in, I feel a strange desire to set the record straight. […]

There is copious evidence that lockdowns reduced transmission of the coronavirus. Some types of social distancing restrictions are more effective than others, and some sub-populations benefit more than others, but overall, lockdowns did limit the spread and saved lives.

That’s hardly a surprising result. The bigger question is, what did lockdown do to the economy? Most people make the natural assumption that lockdown hurts the economy — if you ban people from going out to restaurants, that stops people from spending money on restaurants, right? Obviously. Many economists made this assumption when they tried to model pandemic policy. In fact, some people go so far as to blame all the economic costs of the pandemic on lockdowns. […]

And lo and behold, when we look at evidence, we find that lockdowns accounted for only a small percent of the economic slowdown. For example, economists Austan Goolsbee and Chad Syverson looked at the state border between Illinois and Iowa. On the Illinois side, the towns issued stay-at-home orders, whereas on the Iowa side they did not. And guess what — economic activity fell almost as much on the Iowa side as on the Illinois side!

This is very similar to the results of a comparison of Sweden and Denmark. Denmark locked down and saw its economic activity decline by 29%; Sweden chose not to lock down, and saw its economic activity decline by 25%. The biggest economic destroyer by far was not government policy; it was fear of COVID.

In fact, states that didn’t issue stay-at-home orders in the spring of 2020 saw just about the same amount of economic devastation as states that did issue those orders.

Did the Industrial Revolution decrease costs or increase quality? | Roots of Progress

Note that the price for the highest-quality thread, 100 twist, came down most dramatically. It’s possible for humans to spin thread this fine, but it’s much more difficult and takes longer. For many uses it was prohibitively expensive. But machines have a much easier time spinning any quality of thread, so the prices came closer to equal.

At one level, this is a cost improvement. But don’t assume that the effect for the buyer of thread is that they will spend less money on the same quality of thread. How the buyer responds to a change in the frontier depends on the cost-quality tradeoff they want to make (in economics terms, their elasticity of quality with respect to cost). In particular, the customer may decide to upgrade to a higher-quality product, now that it has become more affordable.

This is what happened in the case of iron, steel, and railroads. In the early decades of railroads, rails were made out of wrought iron. They could not be made from cast iron, which was brittle and would crack under stress (a literal train wreck waiting to happen). But wrought iron rails wore out quickly under the constant pounding of multi-ton trains. On some stretches of track the rails had to be replaced every few months, a high maintenance burden.

Steel is the ideal material for rails: very tough, but not brittle. But in the early 1800s it was prohibitively expensive. […]

Then the Bessemer process came along, a new method of refining iron that dramatically lowered the price of steel. Railroads switched to steel rails, which lasted years instead of months. In other words, what looks like a cost improvement from the supply side, turns into a quality improvement on the demand side.

Stanford researchers make ‘bombshell’ discovery of an entirely new kind of biomolecule | Stanford

Stanford researchers have discovered a new kind of biomolecule that could play a significant role in the biology of all living things.

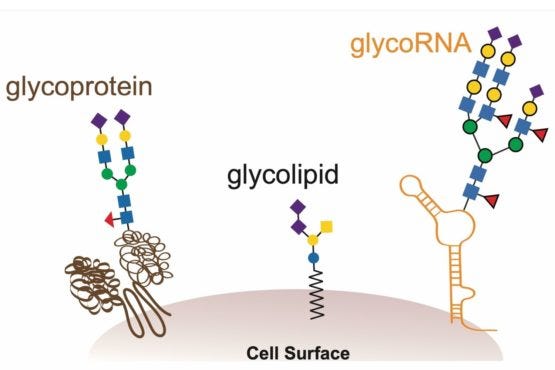

The novel biomolecule, dubbed glycoRNA, is a small ribbon of ribonucleic acid (RNA) with sugar molecules, called glycans, dangling from it. Up until now, the only kinds of similarly sugar-decorated biomolecules known to science were fats (lipids) and proteins. These glycolipids and glycoproteins appear ubiquitously in and on animal, plant and microbial cells, contributing to a wide range of processes essential for life.

The newfound glycoRNAs, neither rare nor furtive, were hiding in plain sight simply because no one thought to look for them – understandably so, given that their existence flies in the face of well-established cellular biology.

'How a $10k poker win changed how I think' | BBC

When amateur player Alex O'Brien unexpectedly won an online poker tournament, little did she know that she'd be pitted against one of the game's most controversial players. A stellar team of poker pros offered to train her, and she discovered how poker can transform how you see the world.

Every child on their own trampoline | The Earthbound Report

When the country went into lockdown last year and the schools closed, I made a parenting decision. I overturned my previous objections and ordered the kids a trampoline. It has been the source of more joy than possibly anything else I have done as a parent. In the sunny days that followed, the children were on it for hours. Work was done uninterrupted as they disappeared into the garden and amused themselves.

However, there are reasons why I didn’t buy them a trampoline the first time they asked. Or the second, or the 34th. There is something that makes me a little uncomfortable about it, and it’s more than the aesthetics or the safety.

Looking out of my daughter’s bedroom window, I can see a grand total of seven different trampolines in back gardens. Almost every family with children has one, of varying sizes and quality. Some are used all the time, some rarely. But it seems to be almost universal now. Every family has its own trampoline.

Meanwhile, the playground round the corner falls apart quietly. It’s usually empty when we go there. When the swings broke years ago, the council took the frame down rather than replace them. […]

Having access to your own things looks like progress, but there is a cost. Community is one of the victims. Shared spaces are places where community happens, where people mix and meet. Nobody makes new friends on their own rowing machine, in front of the TV. Inequality is another. Those who can afford their own won’t notice, but those on lower incomes rely much more on shared resources. When a library closes, it’s those on the margins of society who lose access to books, internet access, or a warm place to sit and do their homework. There is also an environmental cost, as private ownership means endlessly duplicated goods, many underused objects across many owners rather than a few well used objects that are shared.

An Infinite Hotel Runs Out of Rooms | Kottke

This video from Veritasium is a nice explanation of the mathematician David Hilbert’s paradox of the Grand Hotel, which illustrates that a hotel with an infinite number of rooms can still accommodate new guests even when it’s full. Until it can’t, that is.

A Scratched Hint of Ancient Ties Stirs National Furies in Europe | New York Times

Czech archaeologists say marks found on a cattle bone are sixth-century Germanic runes, in a Slavic settlement. The find has provoked an academic and nationalist brawl.

1 star

Building on Tradition — 1,400 Years of a Family Business | Works That Work

Before its liquidation, Kongō Gumi was the oldest continuously operating company in the world. Founded in Japan a mere century after the fall of the Roman Empire, it survived extreme changes in Japan’s culture, government and economy, preserving traditional construction techniques and family values for over 1,400 years.

How Your Hot Showers And Toilet Flushes Can Help the Climate | NPR

A secret cache of clean energy is lurking in sewers, and there are growing efforts to put it to work in the battle against climate change.

The U.S. Department of Energy estimates Americans wash enough energy down the drain every year to power about 30 million homes. The sources are often everyday items inside homes. Think hot showers, washing machines and sinks. Evolving technology is making it easier to harness that mostly warm water.

Denver is now constructing what is likely the largest sewer heat-recovery project in North America, according to Enwave, a Canadian energy company set to operate the system.

Could You Beat a Grizzly Bear in a Fight? Some People Think They Can | Mental Floss

Considering our lack of venom, sharp claws, and all other built-in weapons—not to mention that we have little to no practice fighting wild animals with our bare hands—the doubtfulness expressed in this survey seems logical. But not everyone was so unsure. A full 8 percent of the 1224 participants, which works out to about 98 people, think they’d come out on top against a gorilla, an elephant, or a lion. And about 73 people (6 percent) think they’d win against a grizzly bear.