Links

3 stars

American Hindenburg | Atavist

24-minute read

In the early days of flight, airships were hailed as the future of war. Then disaster struck the USS Akron.

Original link | Archive.is link

JOINT REVIEW: The Ancient City, by Numa Denis Fustel de Coulanges | Mr. and Mrs. Psmith’s Bookshelf

13-minute read

We have a tendency to think of the Greek philosophers as emblematic of their civilization, when in reality they were one of the most bizarre and unrepresentative things that happened in that society. But Numa Denis Fustel de Coulanges is here to tell us it wasn't just the philosophers! So much of our mental picture of Ancient Greece and Rome is actually a snapshot of one fleeting moment in the histories of those places, arguably a very unrepresentative moment at which everything was in the process of collapsing.

[...]

One of my favorite passages in Gibbon's Decline and Fall is in the intro to the chapter on Alaric's invasion of Italy. Gibbon contrasts this with Hannibal's invasion 700 years earlier, and goes on this beautiful riff about how on paper, the Rome of the 5th century AD looks incomparably stronger than that of the 3rd century BC — it had a massively larger population, greater wealth, a greater technological edge over its opponents, etc. And yet when it came to a responsibility as basic as that of defense against a foreign invasion, all the GDP and technology in the world wasn't able to make up for a lack of asabiyyah. When Hannibal annihilated the legions at the Battle of Cannae, something like 20% of the entire adult male population of Rome was killed, including most of her military and political leadership, to which the Romans simply gritted their teeth and raised a few more armies. The descendants of those heroes, despite having a vastly larger population to draw from, weren't able to muster a single legion or a single capable commander, and surrendered their city to the Visigoths almost without a fight.

Museum of Color | Emergence Magazine

16-minute read

From ochre to lapis lazuli, Stephanie Krzywonos opens a door into the entangled histories of our most iconic pigments, revealing how colors hold stories of both lightness and darkness.

Unmasking the Sea Star Killer | bioGraphic

12-minute read

I’m here because this team believes it has unraveled a monumental mystery. In 2013, sea stars began dying along North America’s West Coast, victims of a plague known as sea star wasting disease. The condition first surfaced in the Pacific Northwest, where scientists and scuba divers noticed sea star arms flexing and corkscrewing in tight spirals before tearing off and shimmying away like dancers in some macabre ballet. Grisly lesions, white and splotchy, spread like gangrene across their surfaces. Internal organs seeped from open wounds. Bodies would bloat and then deflate, the muscles dissolving in soupy puddles that left behind flattened sheaths of flesh. These, too, eventually decayed until all that remained were ghostly silhouettes, a sickly residue on the seafloor.

[...]

One day in late 2023, an hour before a scheduled Zoom meeting, the team stumbled on their answer. Gehman’s colleague Melanie Prentice, also with the Hakai Institute and UBC, had begun reviewing the sequencing analysis. Scrolling through data on her laptop, an unmistakable pattern jumped out. Of the hundreds of microorganisms in the samples, enormous quantities of bacteria from the genus Vibrio seemed present in sick stars.

The pattern was so strong, Prentice tells me, that she assumed she’d bungled the analysis. “I’ve definitely done something wrong here,” she recalls thinking. She went back to the beginning.

Litigation Nation, Engineering Empire | Cogitations

33-minute read

This essay analyzes the big idea at the heart of Dan Wang’s new book Breakneck: that China is an “engineering state” facing off against America, the “lawyerly society.” Breakneck is well-informed, creative, and filled with wit. It also hinges heavily on vibes and intuition. Much of the intuition is compelling, but I wanted more data. So I assembled some.

What Is Man, That Thou Are Mindful Of Him? | Astral Codex Ten

5-minute read

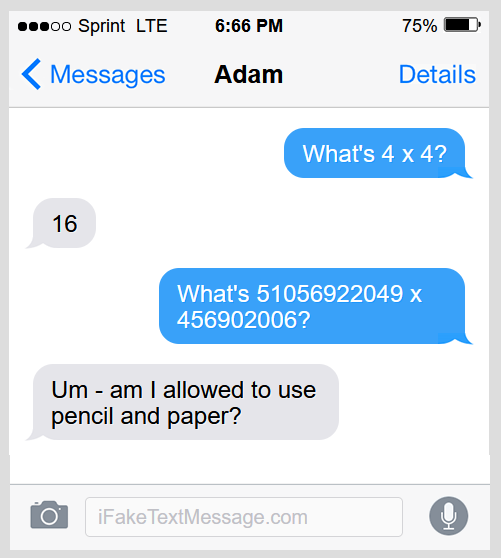

God: …and the math results we’re seeing are nothing short of incredible. This Terry Tao guy -

Iblis: Let me stop you right there. I agree humans can, in controlled situations, provide correct answers to math problems. I deny that they truly understand math. I had a conversation with one of the humans recently, which I’ll bring up here for the viewers … give me one moment …

When I give him a problem he’s encountered in school, it looks like he understands. But when I give him another problem that requires the same mathematical function, but which he’s never seen before, he’s hopelessly confused.

2 stars

How to Build a Medieval Castle | Archaeology Magazine

9-minute read

Sometimes it takes a village to raise a window. Between 2015 and 2017, skilled masons meticulously carved and beveled arches and four-lobed flourishes for a Gothic-style stone window frame in Guédelon Castle’s ornate Chapel Tower. All that remained was to install some glass. But there was a problem, and the carpenters, painters, blacksmiths, basket weavers, historians, and archaeologists who work on-site were all enlisted to figure it out. Eight years later, the matter of what to put in the window of a medieval castle has nearly been resolved…maybe.

Luckily, the team of 40 professional builders and craftspeople at Guédelon Castle love a conundrum. The castle, located in an abandoned quarry in the Puisaye region of Burgundy, 100 miles southeast of Paris, is the site of one of the world’s most comprehensive and longest-running experimental archaeology projects. In this kind of undertaking, archaeologists partner with skilled laborers to test hypotheses about how people worked, lived, and built in the past, filling gaps in academic knowledge through real-world trials. The project launched in 1998 with a straightforward mandate: Build a thirteenth-century castle using only thirteenth-century tools, techniques, and materials. Medieval archaeologists would provide guidance. And the hope was that every obstacle would reveal something that historians, architectural researchers, archaeologists, and castellologues, or scholars who specialize in studying castles, didn’t know.

GDP: We Really Don’t Know How Good We Have It | Asterisk

8-minute read

Everyone loves the hockey stick graph of long-run economic growth. For some, it's the basis of an entire worldview. Unfortunately, the numbers don’t add up.

[...]

All of the Maddison Project estimates for 1 CE come exclusively from a 2009 paper by Walter Scheidel and Steven J. Friesen, who make a valiant latter-day effort to piece together Roman GDP from the fragments of surviving evidence. From the middle of the first to the middle of the second centuries, Scheidel and Friesen have precisely one price of wheat for all of Roman Egypt. For unskilled workers’ wages (measured in terms of wheat), they have three sources: Diocletian’s price edict of 301 CE, papyri from the mid-first to second centuries, and papyri from the mid-third century. Triangulating three sets of estimates from these scattered observations, Scheidel and Friesen arrive at a final total GDP estimate of 50 million tons of wheat at the Empire’s population peak around the mid-second century CE, with a per-capita consumption of 680 kg of wheat or equivalent grains. If we say that subsistence is 390 kg of wheat, and assume that subsistence is worth $400 in 1990 PPP dollars, this translates to $700 in 1990 PPP dollars, giving us the $1,116 in 2011 PPP dollars for 1 CE. (1 CE is still a hundred-odd years off from Scheidel and Friesen’s chosen data point in the mid-second century, but no matter.)

Why Romania Excels in International Olympiads | Palladium

6-minute read

Something else, something more mysterious, explains why Romania is such an outlier in international intellectual competitions. That thing is, in fact, the unique design of the Romanian educational system.

What Does It Mean To Be Thirsty? | Quanta

5-minute read

Water is the most fundamental need for all life on Earth. Not every organism needs oxygen, and many make their own food. But for all creatures, from deep-sea microbes and slime molds to trees and humans, water is nonnegotiable. “The first act of life was the capture of water within a cell membrane,” a pair of neurobiologists wrote in a recent review. Ever since, cells have had to stay wet enough to stay alive.

[...]

But there is a disconnect between drinking water and correcting the water-salt balance. It takes 30 to 60 minutes for water to enter the bloodstream once it’s consumed, and the brain cannot wait that long to figure out if the body has the water it needs. It must make a decision more or less immediately; an animal can’t sit around and do nothing but drink water for half an hour. So, the brain guesses. More of those mysterious sensors kick in. One roughly estimates the volume of water passing through the mouth and throat and sends an initial signal to the brain. A second signal comes from the gut — from specific cell types that respond to water, and even to the mechanical stretching of the stomach as it takes water in. Within a minute, these signals reach the brain and block the neurons in the OVLT and SFO that were activated to trigger thirst. The thirst response shuts off; the throat cools, and the mouth becomes moist again.

Could Lithium Explain — and Treat — Alzheimer’s Disease? | Harvard Medical School

5-minute read

The work, published in Nature, shows for the first time that lithium occurs naturally in the brain, shields it from neurodegeneration, and maintains the normal function of all major brain cell types. The findings — 10 years in the making — are based on a series of experiments in mice and on analyses of human brain tissue and blood samples from individuals in various stages of cognitive health.

The scientists found that lithium loss in the human brain is one of the earliest changes leading to Alzheimer’s, while in mice, similar lithium depletion accelerated brain pathology and memory decline. The team further found that reduced lithium levels stemmed from binding to amyloid plaques and impaired uptake in the brain. In a final set of experiments, the team found that a novel lithium compound that avoids capture by amyloid plaques restored memory in mice.

Could China Have Gone Christian? | Marginal Revolution

1-minute read

Indeed, it is entirely plausible that with only a few turns of history, China might now be the world’s most populous Christian nation. And if that seems hard to believe, consider what did happen. Sixty three years after the fall of Nanjing in 1864, China again erupted into civil war under Mao Zedong. This time the rebels triumphed, and instead of a Christian Heavenly Kingdom the world got a Communist People’s Republic. The parallels are striking: both Hong and Mao led vast zealous movements that promised equality, smashed tradition, and enthroned a single man as the embodiment of truth. Both drew on foreign creeds—Hong from Protestant Christianity, Mao from Marxism-Leninism. Both movement had excesses but of the counter-factual and the factual I have little doubt which promised more ruin.

Eel Mail | Frank Chimero

3-minute read

Today, I learned that eels are fish. This was a disappointment. I knew of fish, I knew of snakes, yet I always assumed eels were some secret third thing. But, nope, they’re just fish. Or are they? A little digging revealed that eels are deeply weird fish, and to my great satisfaction, the secrets I sensed in them run stranger and deeper than their “fish” label suggests.

1 star

Our Shared Reality Will Self-Destruct in the Next 12 Months | The Honest Broker

4-minute read

At the current rate of technological advance, all reliable ways of validating truth will soon be gone. My best guess is that we have another 12 months to enjoy some degree of confidence in our shared sense of reality.

Teenager with hyperthymesia exhibits extraordinary mental time travel abilities | Psychology News

3-minute read

TL’s recollections were not merely accurate—they were structured. She described a highly organized internal world where memories were stored in a large, rectangular “white room” with a low ceiling. Within this mental space, personal memories were arranged thematically. Sections were dedicated to family life, vacations, friends, and even her collection of soft toys. Each toy had its own memory tag, including information about when and from whom it was received.

Mars’s interior more like Rocky Road than Millionaire’s Shortbread | Imperial College London

3-minute read

Seismic vibrations detected by NASA's InSight mission revealed subtle anomalies, which led scientists from Imperial College London and other institutions to uncover a messier reality: Mars's mantle contains ancient fragments up to 4km wide from its formation - preserved like geological fossils from the planet's violent early history.

A new mega-earthquake hotspot could be forming beneath the Atlantic | BBC

2-minute read

For centuries, scientists have puzzled over why Portugal has suffered huge earthquakes despite lying far from the world’s major fault lines.