Links

3 stars

A Thrive / Survive Theory of the Political Spectrum | Slate Star Codex

From 2013, but I must have missed it the first time around…

My hypothesis is that rightism is what happens when you’re optimizing for surviving an unsafe environment, leftism is what happens when you’re optimized for thriving in a safe environment. […]

I propose that the best way for leftists to get themselves in a rightist frame of mind is to imagine there is a zombie apocalypse tomorrow. It is a very big zombie apocalypse and it doesn’t look like it’s going to be one of those ones where a plucky band just has to keep themselves alive until the cavalry ride in and restore order. This is going to be one of your long-term zombie apocalypses. What are you going to want? […]

What about the opposite? Let’s imagine a future utopia of infinite technology. Robotic factories produce far more wealth than anyone could possibly need. The laws of Nature have been altered to make crime and violence physically impossible (although this technology occasionally suffers glitches). Infinitely loving nurture-bots take over any portions of child-rearing that the parents find boring. And all traumatic events can be wiped from people’s minds, restoring them to a state of bliss. Even death itself has disappeared. What policies are useful for this happy state?

Triple Tragedy And Thankful Theory | Astral Codex Ten

This piece is effectively a follow-up to the piece above.

I accept guest posts from certain people, especially past Book Review Contest winners. Earlier this year, I published Daniel Böttger’s essay Consciousness As Recursive Reflections.

While we were working on editing it, Daniel had some dramatic experiences and revelations, culminating in him developing a theory which he says “will contribute to saving the world”, which he asked me to publish.

Although I can’t speak for its world-historical importance, and although he admits his mental state is fragile, after some discussion I decided to publish because - if nothing else - he’s a great writer with a fascinating story and some really interesting thoughts. […]

This is the theory: Survival-oriented systems are trying to be space-efficient rather than time-efficent, because they are at constant risk of mental memory (especially the phonological loop) getting overwritten by catastrophically urgent new data, and because this risk is strongly positively correlated to how urgently they need to act. The rest is commentary.

Enterprise Philosophy and The First Wave of AI | Stratechery

Classic Ben Thompson (in both good ways and bad) — a sprawling but highly intelligent piece on how AI might affect business:

If, however, you believe that AI is not just the next step in computing, but rather an entirely new paradigm, then it makes sense that enterprise solutions may be back to the future. We are already seeing that that is the case in terms of user behavior: the relationship of most employees to AI is like the relationship of most corporate employees to PCs in the 1980s; sure, they’ll use it if they have to, but they don’t want to transform how they work. That will fall on the next generation.

Executives, however, want the benefit of AI now, and I think that benefit will, like the first wave of computing, come from replacing humans, not making them more efficient. And that, by extension, will mean top-down years-long initiatives that are justified by the massive business results that will follow. That also means that go-to-market motions and business models will change: instead of reactive sales from organic growth, successful AI companies will need to go in from the top. And, instead of per-seat licenses, we may end up with something more akin to “seat-replacement” licenses (Salesforce, notably, will charge $2 per call completed by one of its agents). Services and integration teams will also make a comeback. It’s notable that this has been a consistent criticism of Palantir’s model, but I think that comes from a viewpoint colored by SaaS; the idea of years-long engagements would be much more familiar to tech executives and investors from forty years ago.

REVIEW: Science in Traditional China, by Joseph Needham | Mr. and Mrs. Psmith’s Bookshelf

REVIEW: Math from Three to Seven, by Alexander Zvonkin | Mr. and Mrs. Psmith’s Bookshelf

Stumbled across this delightful Substack.

There’s an old trope that the Chinese invented gunpowder and had it for six hundred years, but couldn’t see its military applications and only used it for fireworks. I still see this claim made all over the place, which surprises me because it’s more than just wrong, it’s implausible to anybody with any understanding of human nature. […]

All told it’s about three and a half centuries from the first sage singing his eyebrows, to guns and cannons dominating the battlefield. Along the way what we see is not a gaggle of childlike orientals marveling over fireworks and unable to conceive of military applications. We also don’t see an omnipotent despotism resisting technological change, or a hidebound bureaucracy maintaining an engineered stagnation. No, what we see is pretty much the opposite of these Western stereotypes of ancient Chinese society. We see a thriving ecosystem of opportunistic inventors and tacticians, striving to outcompete each other and producing a steady pace of technological change far beyond what Medieval Europe could accomplish.

Yet despite all of that, when in 1841 the iron-sided HMS Nemesis sailed into the First Opium War, the Chinese were utterly outclassed. For most of human history, the civilization cradled by the Yellow and the Yangtze was the most advanced on earth, but then in a period of just a century or two it was totally eclipsed by the upstart Europeans. This is the central paradox of the history of Chinese science and technology. So… why did it happen?

To me, one of the greatest historical puzzles is why the Cold War was even a contest. Consider it a mirror image of the Needham Question: Joseph Needham famously wondered why it was that, despite having a vastly larger population and GDP, Imperial China nevertheless lost out scientifically to the West. […] Well, with the Soviets it all went in the opposite direction: they had a smaller population, a worse starting industrial base, a lower GDP, and a vastly less efficient economic system. How, then, did they maintain military and technological parity with the United States for so long?

The puzzle was partly solved for me, but partly deepened, when those of us who grew up in the ‘90s and ‘00s encountered the vast wave of former Soviet émigrés that washed up in the United States after the fall of communism. Anybody who played competitive chess back then, or who participated in math competitions, knows what I’m talking about: the sinking feeling you got upon seeing that your opponent had a Russian name. […]

When I related these questions to an Ashkenazi-supremacist friend of mine, he immediately suggested that “maybe it’s because they’re all Jewish.” (I’ve noticed that the most philosemitic people and the most antisemitic people sometimes have curiously similar models of the world, they just disagree on whether it’s a good thing.) My friend’s question wasn’t crazy, since there are definitely times when asking “were they all Jewish?” yields an affirmative answer. But in this case I had to disappoint him with the knowledge that many of these Russian math and chess superstars were gentiles. What’s more, by the ‘60s and ‘70s the Soviets had an entire discriminatory apparatus dedicated to keeping Jews out of the scientific establishment, so it would be impressive indeed if they were the foundation of its success.

Pivot Points | A Smart Bear

“Competitive” is a fact-of-the-matter of my personality. It’s a thing that exists, outside of judgement. I call this non-judgmental fact a Pivot Point because of how you can use them to win at life and business. The rest of this article explains how to do that.

Pivot Points are strengths in some situations, hinderances in others, and irrelevant in still others. This is why I don’t like the ideas of “strengths” and “weaknesses” generally—whether in personality tests or SWOTs or other tools of strategy and planning. Those frameworks imply that we already know the context for evaluation, but often we don’t. Pivot Points are neither intrinsically good nor bad, they just are.

But why the word “Pivot”?

Because you’re “stuck there” like your “pivot foot” in games like basketball and lacrosse and Ultimate Frisbee. Your other foot—and the rest of your body—is free to move anywhere, subject to that constraint. This is the correct metaphor for using Pivot Points in life and strategy. These are the constraints you build around. For example if you hate managing people (Pivot Point), you shouldn’t become a manager, nor should you make a company that will eventually require a team, or you shouldn’t be the CEO of that company.

The other reason is that Pivot Points can change, but not often, and not capriciously. Sometimes you pick up your foot, run somewhere else, and establish a new pivot; this is investing in a new skill, or learning a new industry, or overcoming something that’s a weakness relative to your goals. Short-term planning should assume Pivot Points are fixed, because in the short term, they are. Long-term planning, especially when deciding where to investing your time and money, can ask: What new Pivot Points do we want?

The Problem with Effective Altruism | Yascha Mounk

As someone who still sort of calls himself an effective altruist (emphasis on the “sort of”), I found myself agreeing wholeheartedly:

When I was a visiting fellow at Oxford two years ago, I heard a story about effective altruism I keep going back to whenever somebody mentions Sam Bankman-Fried (one of the philosophy’s early champions) or colonizing Mars (one of its advocates’ principal obsessions).

According to the story, a classmate lent one of the most vocal advocates for effective altruism her toaster while they were both graduate students at Oxford. She reminded him to return it a week later, and a month later, and three months later, to no avail. Finally, invited to his apartment for a social gathering, she spotted the toaster on the kitchen counter, covered in mold.

“Why on earth didn’t you return the toaster to me?” she asked, in frustration.

“I ran the numbers,” he responded. “If I want to do good for the world, my time is better spent working on my thesis.”

“Couldn’t you at least have cleaned the damn thing?”

“From a moral point of view, I’m pretty sure the answer is no.”

I have no idea whether the story is true. Being just a little too perfect, I suspect that it is probably exaggerated, and possibly completely made up. But I share it here because the attitude it encapsulates goes to the core of how the movement of effective altruism went wrong—and why the original intuition that gave rise to it might just be worth rehabilitating.

2 stars

Preliminary Milei Report Card | Astral Codex Ten

How is Javier Milei, the new-ish libertarian president of Argentina doing?

According to right-wing sources, he’s doing amazing, inflation is vanquished, and Argentina is on the road to First World status.

According to left-wing sources, he’s devastating the country, inflation has ballooned, and Argentina is mired in unprecedented dire poverty.

I was confused enough to investigate further.

My October 7 post | Shtetl-Optimized

What could I do to break through? What could I say to all the people who call themselves “anti-Israel but not antisemitic” that would actually move the conversation forward?

Finally I came up with something. Look: you say you despise Zionism, and consider October 7 to have been perfectly understandable (if somewhat distasteful) resistance by the oppressed? Fine, then.

I urge you to lobby your country to pass a law granting automatic refugee status and citizenship to any current citizen of Israel—as an ultimate insurance policy to incentivize Israel to take greater risks for peace, even with neighbors who openly proclaim the Jews’ extermination as their goal.

OpenAI just unleashed an alien of extraordinary ability | Understanding AI

OpenAI says the “o” just stands for OpenAI, though some people joked that it’s a reference to the O-1 visa, which the US government grants to “aliens of extraordinary ability.”

I don’t think the o1 models are a threat to humanity, but they really are extraordinary.

Over the last nine months I’ve written a number of articles about new frontier models: Gemini 1.0 Ultra, Claude 3, GPT-4o, Claude 3.5 Sonnet and Gemini Pro 1.5, and Grok 2 and Llama 3.1. I was more impressed by some of these models and less impressed by others. But none of them were more than incremental improvements over the original GPT-4.

The o1 models are a different story. o1-preview aced every single one of the text-based reasoning puzzles I’ve used in my previous articles. It’s easily the biggest jump in reasoning capabilities since the original GPT-4.

Who died and left the US $7 billion? | Sherwood

It was the biggest estate-tax payment in modern history, but no one knew who made it. Then an anonymous phone call pointed to one man.

Italian mannerism, David Lynch, and Lars von Trier | The Pursuit of Happiness

I’ve heard people suggest that it was a sort of miracle that there were so many artistic geniuses in Italy right around 1500. Well, economists are the sort of people who tell little children that Santa doesn’t exist, and I’m here to tell you that there was no miraculous clustering of talent in Italy. The world is full of geniuses.

But there was a flowering of artistic greatness, and we need to understand why.

Between 1500 and 1550, great paintings were produced by people like Titian, Tintoretto, Veronese, Bellini, Giorgioni, Leonardo, Michelangelo, Raphael, Bottecelli and del Sarto, among others. All of these Italian masters lived in a country of about 10 million people, the population of Ohio. Who are Ohio’s top ten painters? […]

You probably think I’m one of those tech guys that denigrates art and insists that AI can do just as well. Nope, just the opposite. Those tech guys don’t understand the nature of great art. Italy really did produce a lot of great art. Eighteenth century Germany/Austria really did produce a lot of great music. But why?

The key is to understand the difference between artistic talent, which is not uncommon, and artistic greatness, which requires talent and a very special set of circumstances.

Do AI companies work? | benn.substack

The market needs to be irrational for you to stay solvent. […]

Therefore, if you are OpenAI, Anthropic, or another AI vendor, you have two choices. Your first is to spend enormous amounts of money to stay ahead of the market. This seems very risky though: The costs of building those models will likely keep going up; your smartest employees might leave; you probably don’t want to stake your business on always being the first company to find the next breakthrough. Technological expertise is rarely an enduring moat.

Your second choice is…I don’t know? Try really really hard at the first choice?

Explorer Shackleton’s lost ship as never seen before | BBC News

After more than 100 years hidden in the icy waters of Antarctica, Sir Ernest Shackleton’s ship Endurance has been revealed in extraordinary 3D detail.

Archaeologists use AI to discover 303 unknown geoglyphs near Nazca Lines | The Guardian

Newly discovered figures dating back to 200BCE nearly double the number of known geoglyphs at enigmatic site

1 star

Batting by the Numbers | The Pudding

For most of baseball history, there was a set pattern of roles in the batting lineup, passed down to managers through decades of experience. But those rules are changing as baseball evolves, especially with analytics increasingly guiding decisions. The 1993 Blue Jays might not look the same in 2024.

Photos: Building Human Towers in Spain | The Atlantic

In Tarragona, Spain, more than 40 teams of “castellers” recently gathered for the city’s 29th biannual human-tower competition—working together to build the highest and most complex human towers (castells) possible. Winning teams reached as high as 10 tiers above the ground. Gathered here are some of the images of these amazing structures, and the effort involved in forming them.

"Everyone Gains": The Pretty Lie of Economics | Bet On It

Yet in the heart of our sanctuary of ugly truths, economists have long cultivated a very special pretty lie. One almost unique to our intellectual world. Namely: Pointing to a change that is good on balance, then absurdly claiming that “everyone gains.” Stock examples:

“Everyone gained from the Industrial Revolution.”

“Everyone gained from the Internet.”

“Everyone would gain from congestion pricing.”

“Everyone gains from free trade.”

Even as hard-headed an economist as Milton Friedman lapsed into this pretty lie back in 1978: “If you have free immigration in the way in which we had it before 1914, everybody benefited.” Seriously, Milton?!

Thousands of bones and hundreds of weapons reveal grisly insights into a 3,250-year-old battle | CNN

A new analysis of dozens of arrowheads is helping researchers piece together a clearer portrait of the warriors who clashed on Europe’s oldest known battlefield 3,250 years ago.

The Distorted Paper Collages of Lola Dupré | Kottke

Collage artist Lola Dupré makes these wonderfully weird images of exaggerated objects, animals, and people.

Graveyard vs. Cemetery: What’s the Difference? | Mental Floss

The words’ meanings have changed over time—and there are a few distinctions between the places themselves.

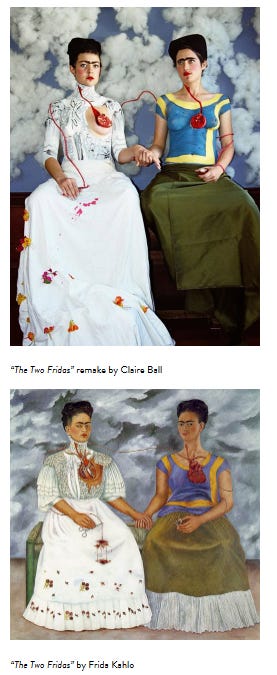

Remake / Submissions | Booooooom

Are there any planets in the universe that aren't round? | LiveScience

One such body is the exoplanet WASP-103 b, a gas giant twice the size of Jupiter and 1.5 times its mass that orbits a star nearly twice as large as the sun.

WASP-103 b is also "really, really close to the star," Barros said. That changes its shape. "There's a balance between the force of the gas that's called the hydrostatic equilibrium, that wants to expand the planet … and the strength of the gravitational attraction." This pull from the host star leads to a planet that's "tear-shaped," Barros said.